Canine Reactive Histiocytoses

Reactive histiocytoses - general considerations

Reactive histiocytoses have been described in dogs; a feline counterpart has not been recognized to date. Reactive histiocytoses are either confined to skin and draining lymph nodes (CH) or involve skin and extracutaneous sites (SH). Systemic histiocytosis was first described in Bernese mountain dogs, and a familial association was apparent (Vet Pathol. 1984;21(6):554–563). Histiocytic sarcomas occurred in the same families of Bernese mountain dogs as SH, but progression of SH to HS was not observed (Vet Pathol. 1986;23(1):1–10). Systemic histiocytosis occurs in many other large breeds of dogs. Overall, SH is a rare disease and CH is far more common. Cutaneous histiocytosis was first described in dogs as a waxing and waning dermatitis and panniculitis of unknown etiology, in which the lesions were dominated by histiocytes(J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;188:377–381).

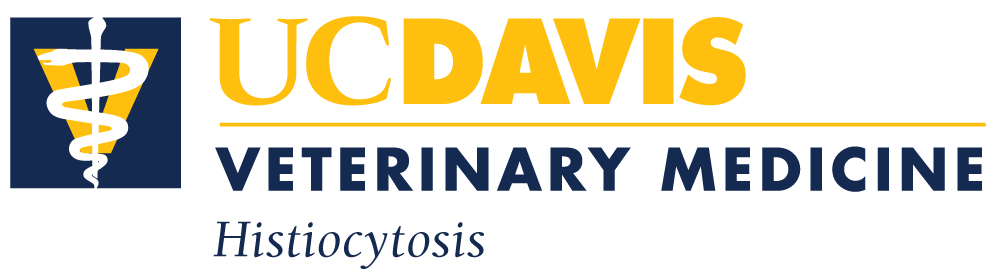

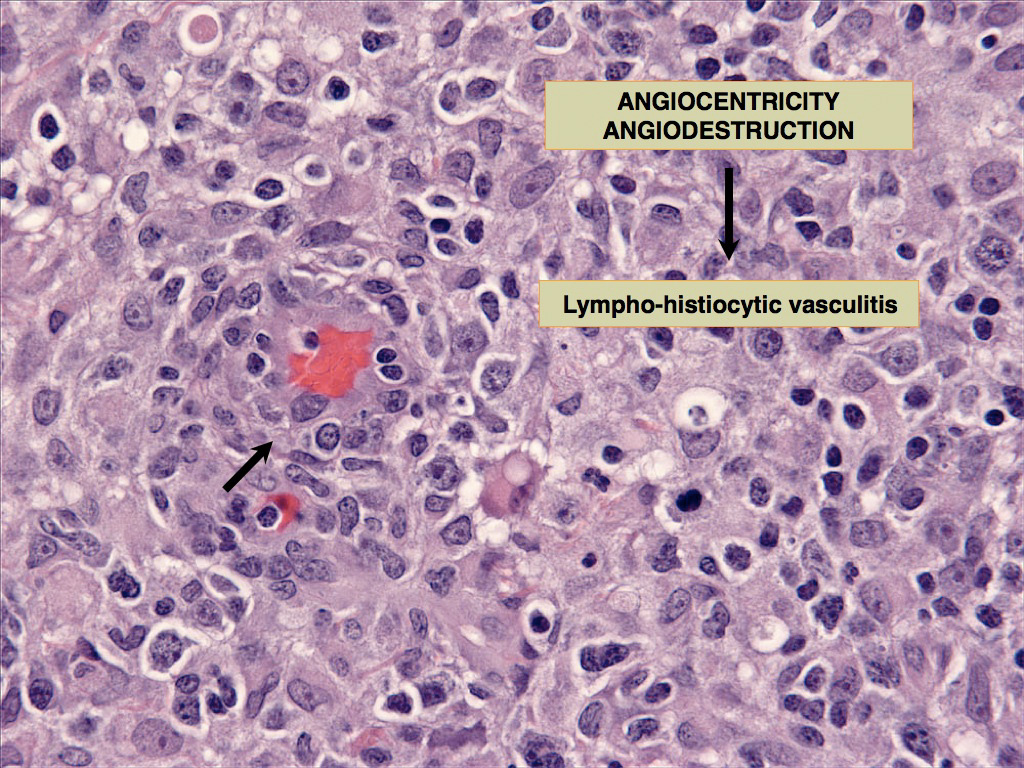

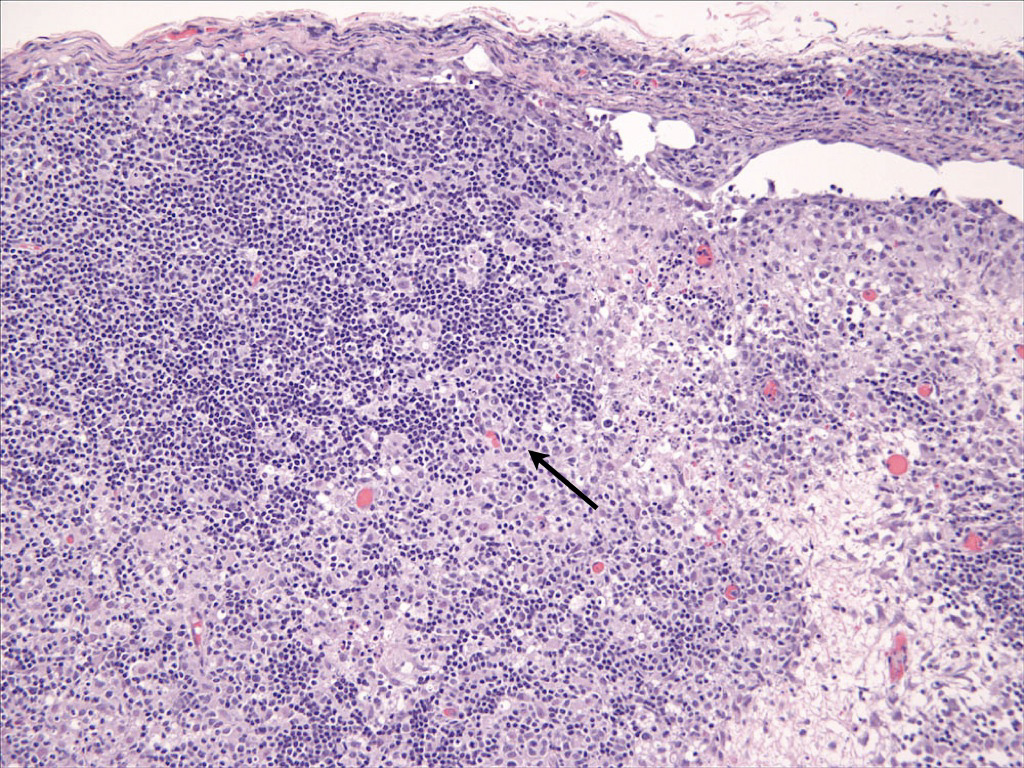

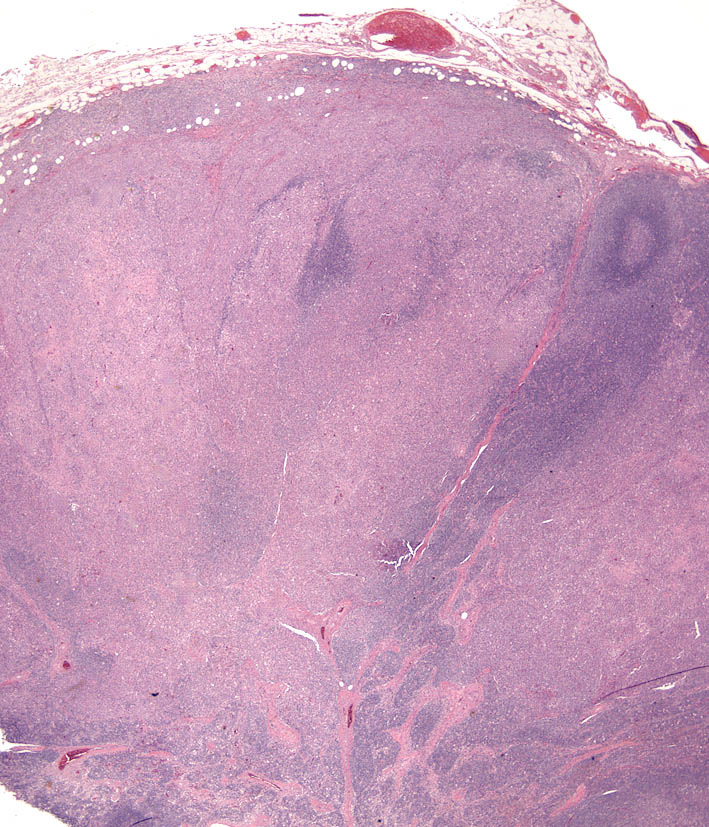

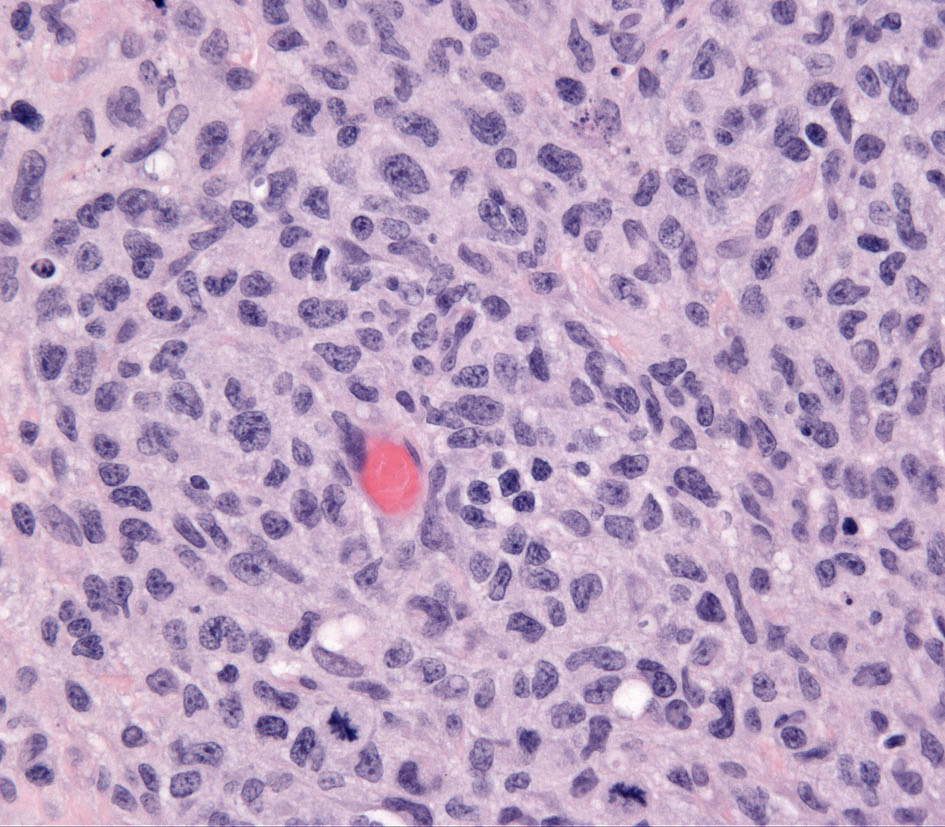

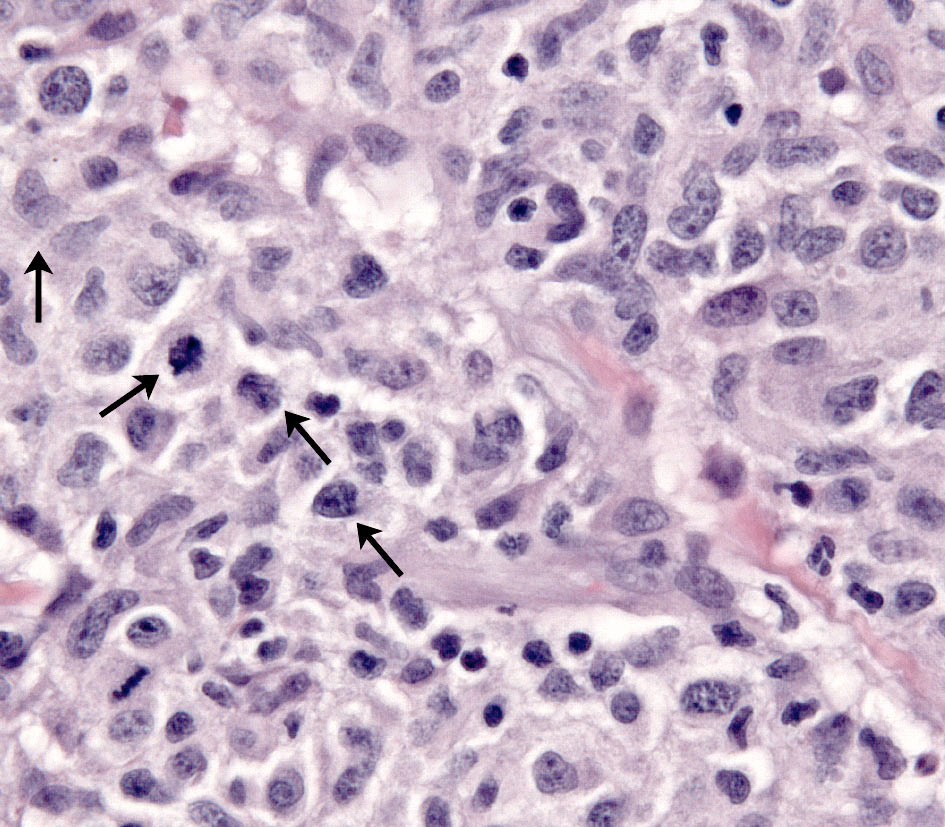

The concept that CH and SH are related diseases emerged from an study in which an identical lesion topography and histiocyte immunophenotype was described in CH and SH (Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(1):40–48). Cutaneous and systemic histiocytosis are related histiocytic inflammatory diseases that are believed to have an element of immune dysregulation in their pathogenesis. The lesions are thought to be antigen driven, but no etiologic agent/antigen has been discovered. The lesions are dominated by activated dermal interstitial DCs and T cells, which frequently infiltrate the walls of dermal vessels creating a lympho-histiocytic vasculitis (Fig. 1- arrow) . The lesions radiate from affected vessels and coalesce to form masses, especially in the deep dermis and panniculus. Therefore, the lesions have a “bottom-heavy” topography (Fig. 2), and should never be confused with histiocytomas, which have a “top-heavy” topography.

Cutaneous histiocytosis

Cutaneous histiocytosis is an inflammatory lympho-histiocytic proliferative disorder that primarily involves skin and subcutis. CH occurs in a number of breeds; there is no clear breed predisposition. Lesions may extend to involve the local lymph nodes, which are part of the skin immune system. The incidence of lymph node involvement is unknown, since lymph nodes are not commonly sampled when skin biopsies are taken unless there is marked lymphadenomegaly. The lesions most often occur as multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules up to 4 cm diameter; solitary lesions are uncommon. Overlying skin ulceration is common. Lesions may disappear spontaneously, or regress and appear at new sites simultaneously. Topographically, lesions may be found on the face, nose, neck, trunk, extremities (including foot pads), perineum and scrotum (Fig. 3). Morphological features of CH are similar to those of SH in skin, so they will be described together.

-TOP-

Systemic histiocytosis

Systemic histiocytosis was originally described in related Bernese Mountain Dogs. SH has been observed in other breeds less commonly (Rottweiler, Labrador retriever, Basset hound, Irish wolfhound and others). Familial occurrence of SH is evident in Irish wolfhounds in the Pacific northwest (USA) (Moore, PF – unpublished observations).

SH is a generalized histiocytic proliferative disease with a marked tendency to involve skin, ocular and nasal mucosae, and peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 4). The disease predominately affects young to middle aged dogs (2-8 years). Clinical signs vary with the severity and extent of the disease and may include anorexia, marked weight loss, stertorous respiration and conjunctivitis with marked chemosis. Multiple cutaneous nodules may be distributed over the entire body, but are especially prevalent in the scrotum, nasal apex, nasal planum and eyelids. These are are similar sites in which CH occurs. Ulceration of the skin overlying the nodules is common. Peripheral lymph nodes may be palpably enlarged by the histiocytic infiltrates. The disease course may be punctuated by remissions and relapses, which may occur spontaneously especially early in the disease course.

Morphologic features - reactive histiocytoses

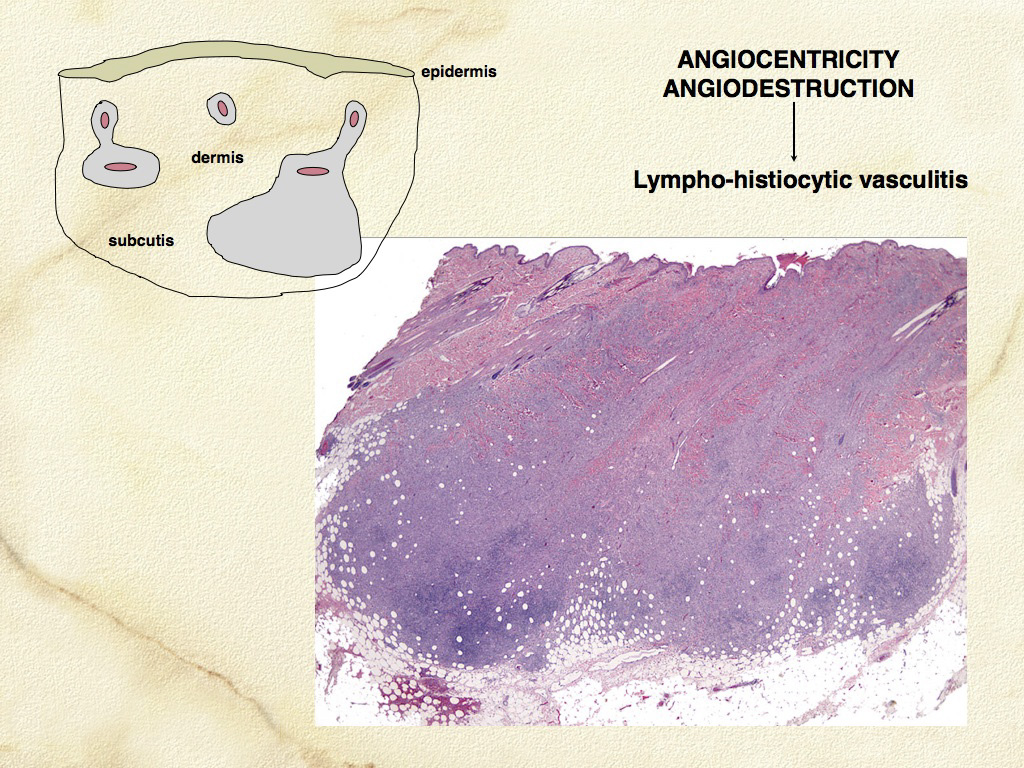

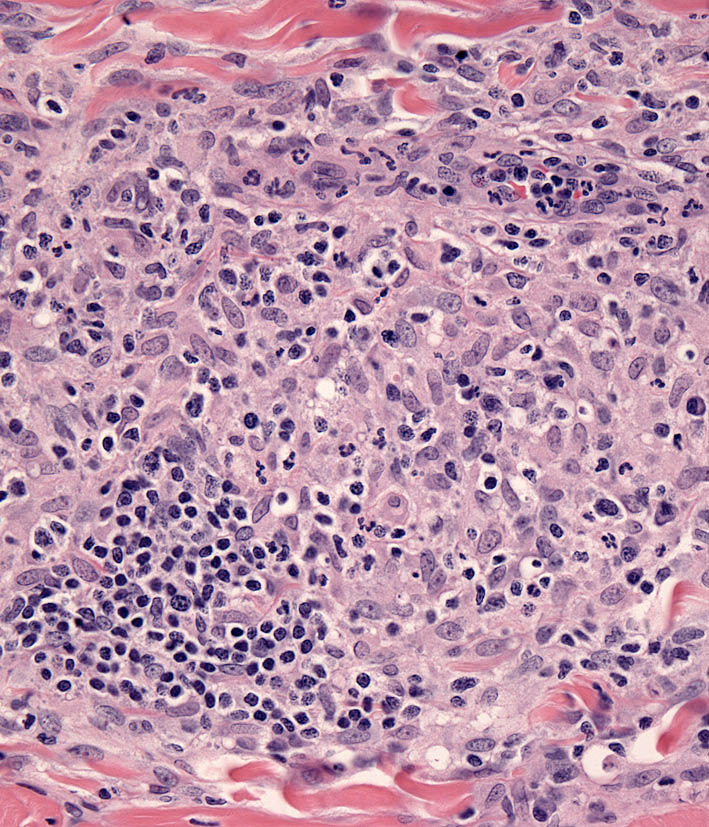

Microscopic features of SH and CH are essentially identical in skin. The lesions usually extensively involve the deep dermis and subcutis. Discrete perivascular lesions affecting the mid-dermis often coalesce in the deep dermis and subcutis. Involvement of the superficial dermis is inconsistent and epidermotropism by histiocytes is unusual. Overall, the lesions have “bottom heavy” topography (see figure above). Histiocytes and lymphocytes frequently invade vessel walls (i.e. lympho-histiocytic vasculitis), and this may lead to vascular compromise and infarction of surrounding tissues, which contributes to ulceration of the cutaneous lesions in CH and SH (Fig. 5). The infiltrate is pleo-cellular, but histiocytes and lymphocytes are more numerous than neutrophils, plasma cells and eosinophils (Fig. 6).

Histiocytes have large round to oval, indented, folded or twisted nuclei. Histiocytes have abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with occasional vacuoles. Multinucleated histiocytes and histiocytes with bizarre, misshapen nuclei and mitotic figures, which are characteristic of HS, are lacking in CH and SH. Lesions may occur aining in skin drlymph nodes in CH and SH. Histiocytes selectively invade the paracortex and sinuses (Fig. 7. In severe lesions, the cortex is obliterated by histiocytic infiltration, which also effaces lymph node trabeculi and the capsule (Fig. 8) Significant perinodal infiltration is possible.

Inflamed cutaneous non-epitheliotropic T cell lymphoma is readily confused with CH (see neCTCL below). Beyond the skin, the widespread distribution of the lesions of SH is only fully appreciated at necropsy. Histiocytic lesions have been observed in lung, liver, bone marrow, spleen, peripheral and visceral lymph nodes, kidneys, testes, orbital tissues, nasal mucosa and other sites. The lesions in these sites are vaso-centric, and the infiltrates radiate to obliterate surrounding tissue. The lesions may only be microscopic, but mass formation has also been observed.

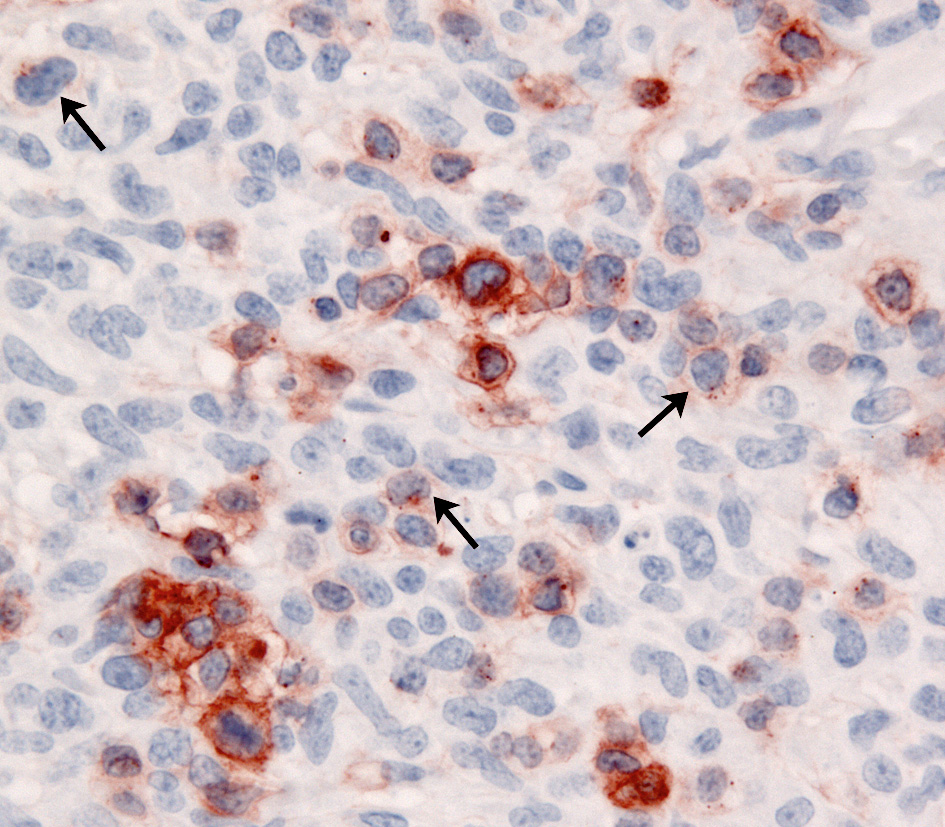

Immunophenotypic features

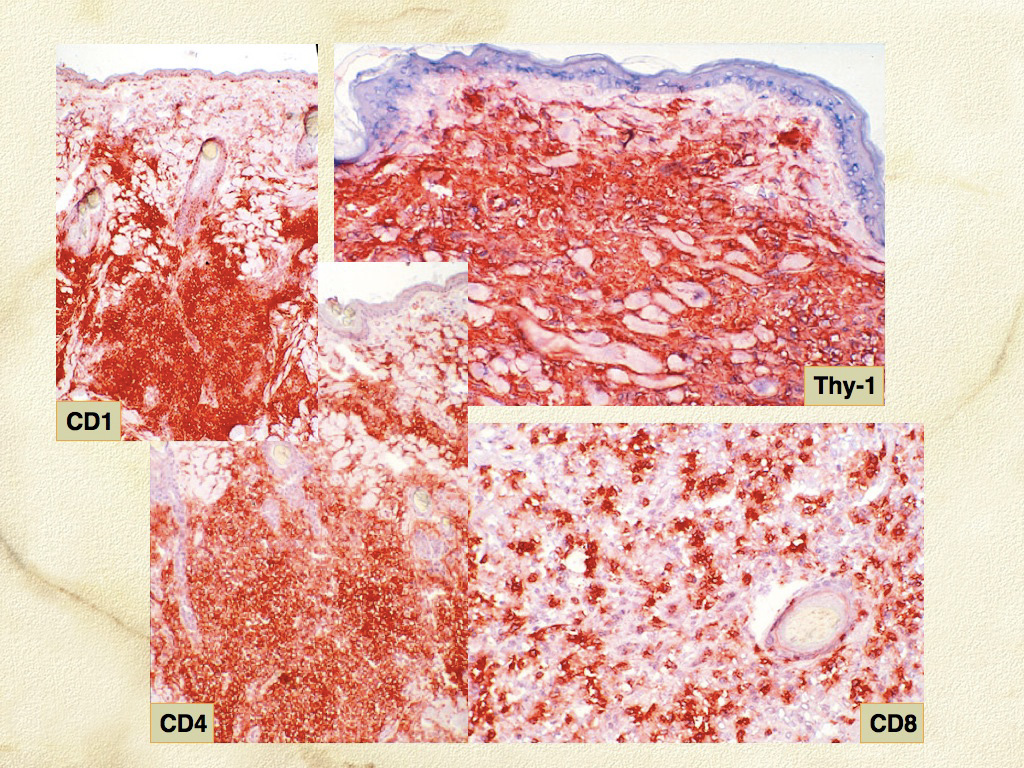

The immunophenotypic expression pattern of SH and CH are virtually identical. Histiocytes in SH and CH express markers expected of DCs such as CD1a, C11c/CD18 and MHC class II. Histiocytes express CD4 (a marker of DC activation) and CD90 (Thy-1), which is expressed by normal dermal interstitial DCs. Histiocytes lack expression of E-cadherin. Hence, the immunophenotype of histiocytes in CH and SH is the inverse of that seen in cutaneous histiocytoma and cutaneous LCH with respect to the expression of CD4, CD90 and E-cadherin. The activated interstitial DC immunophenotype of CH and SH is not observed in HS – CD4 expression has not been encountered to date. Unfortunately, CD1a, CD4 and CD11c are not assessable in formalin fixed tissue sections. CD90, CD18, MHC class II and E-cadherin are assessable in formalin-fixed tissue sections.

-TOP-

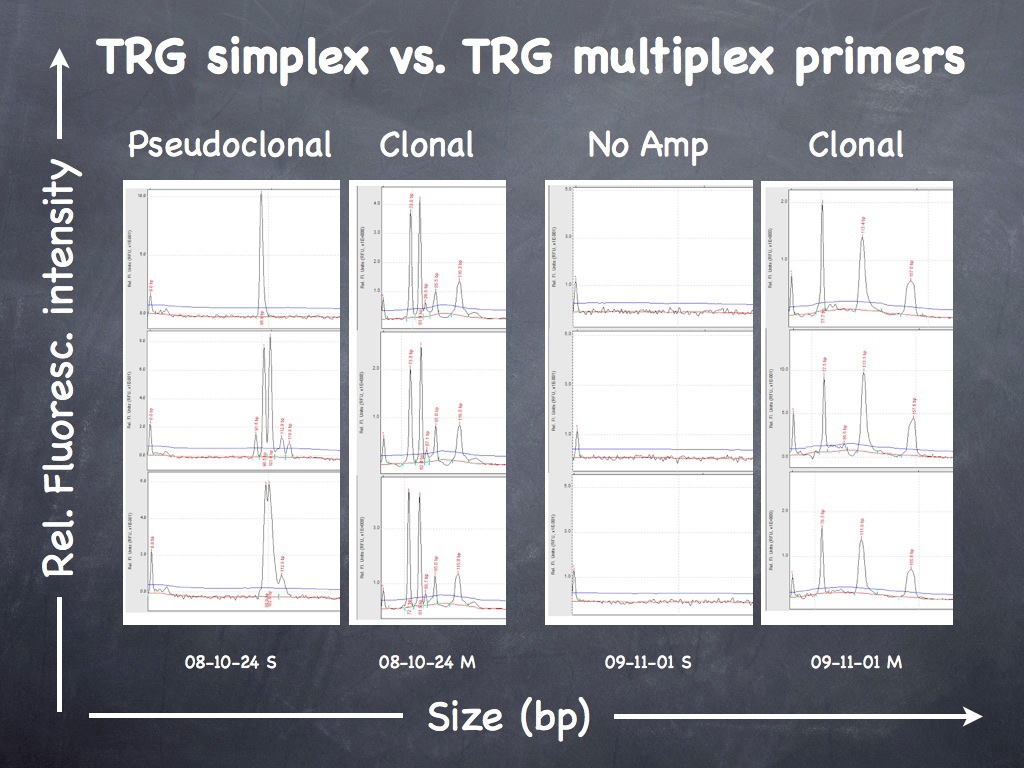

Reactive histiocytosis vs Inflamed non-epitheliotropic CTCL

Inflamed cutaneous non-epitheliotropic T cell lymphoma (neCTCL) is readily confused with CH. The key discriminatory features are identification of clusters of cytologically atypical T cells, and variable expression of CD3 by neoplastic T cells – so called “CD3 antigen loss”. Definitive diagnosis is reliant upon T cell receptor gamma (TRG) gene rearrangement analysis, which will detect clonal T cell expansion of the lymphoma cells within the reactive/inflammatory T cell and histiocyte infiltration.

-TOP-