General Considerations

Histiocytic Sarcoma Complex - General Considerations

Histiocytic sarcomas (HS) are most often derived from cells with the phenotypic profile of interstitial DCs. The reactive histiocytoses (CH and SH) are complex inflammatory disorders composed of lymphocytes and activated interstitial DCs. Interstitial DCs occur in almost all tissues with the exception of the brain. Interstitial DCs do occur in the meninges and choroid plexi. Interstitial DCs are identifiable in tissues by immunophenotyping.

Given the ubiquitous distribution of interstitial DCs, HS can arise in almost any tissue. The neoplastic cells in the majority of canine HS lesions have been shown to express an immunophenotype consistent with an interstitial DC origin. Histiocytic sarcomas may be localized, i.e. they originate at a single tissue site or in a single organ (with solitary or multiple foci). Once the lesions spread beyond the local draining lymph node to involve distant sites, the disease is then considered disseminated HS. Disseminated HS is the currently accepted terminology for what was originally reported as malignant histiocytosis. Localized and disseminated HS have been observed in cats at a far lower incidence than in dogs. In essence, feline HS complex resembles the canine counterpart in terms of location of lesions and disease progression.

The HS complex of diseases was first recognized in Bernese mountain dogs, in which a familial association was apparent. Pedigree analyses support a polygenic mode of inheritance in Bernese mountain dogs. Other breeds are predisposed to HS complex diseases and these include Rottweilers, Golden retrievers, and Flat-coated retrievers. HS complex is not limited to just these breeds and can occur sporadically in any breed. Recently, studies of the genomic loci involved in HS in Bernese mountain dogs and flat-coated retrievers have pointed to abnormalities in tumor suppressor gene loci (CDKN2A/B, RB1 and PTEN) that are broadly similar to those described in human HS. Other genomic loci are probably involved as well.

Clinical signs of HS are vague and include anorexia, weight loss, and lethargy. Other signs depend on the organs involved and are a consequence of destructive mass formation. Accordingly, pulmonary symptoms such as cough and dyspnea have been seen. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement (primary or secondary) can lead to seizures, incoordination and paralysis. Lameness is often observed in articular HS. Dogs with HS of interstitial DC origin often have mild, non-regenerative anemia. More severe regenerative anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia and hypocholesterolemia has been consistently documented in hemophagocytic HS. Hypercalcemia may also be encountered with HS, although the incidence is low (3%).

Morphologic Features

Primary lesions of HS occur in spleen, lymph node, lung, bone marrow, CNS, skin and subcutis, and in periarticular and articular tissues of the limbs. Secondary sites are widespread, but consistently include liver and lungs (with splenic primary), and hilar lymph nodes (with lung primary). In the original report of HS in Bernese mountain dogs, a high incidence of primary lung lesions was apparent. Pulmonary HS may have been mistaken for anaplastic large cell carcinoma of the lung before the advent of cell markers for lineage determination. Similarly, about 50% of synovial tumors of dogs were shown to be localized HS by utilizing an anti-canine CD18 monoclonal antibody (LABL), which retained reactivity in formalin-fixed tissue sections.

Lesions of HS that originate from interstitial DCs (see below) are typically destructive mass lesions with a uniform, smooth cut surface and are white/cream to tan in color (Fig. 1 top). Lesions may be solitary or multiple within an organ (especially spleen). Articular HS has a distinctive appearance: it occurs as multiple tan nodules located beneath the synovial lining; these are further described below.

Hemophagocytic HS, which originates from macrophages (see below), does not initially form mass lesions in the primary sites (spleen and bone marrow). Typically, diffuse splenomegaly is consistently observed. Within the grossly enlarged spleen, ill-defined mass lesions may be perceptible as well (Fig. 1 bottom). Hemophagocytic HS may coincide with HS of interstitial DC origin. In these instances, both diffuse splenomegaly and discrete mass formation are observed. Lesions of this nature cause the most confusion for pathologists.

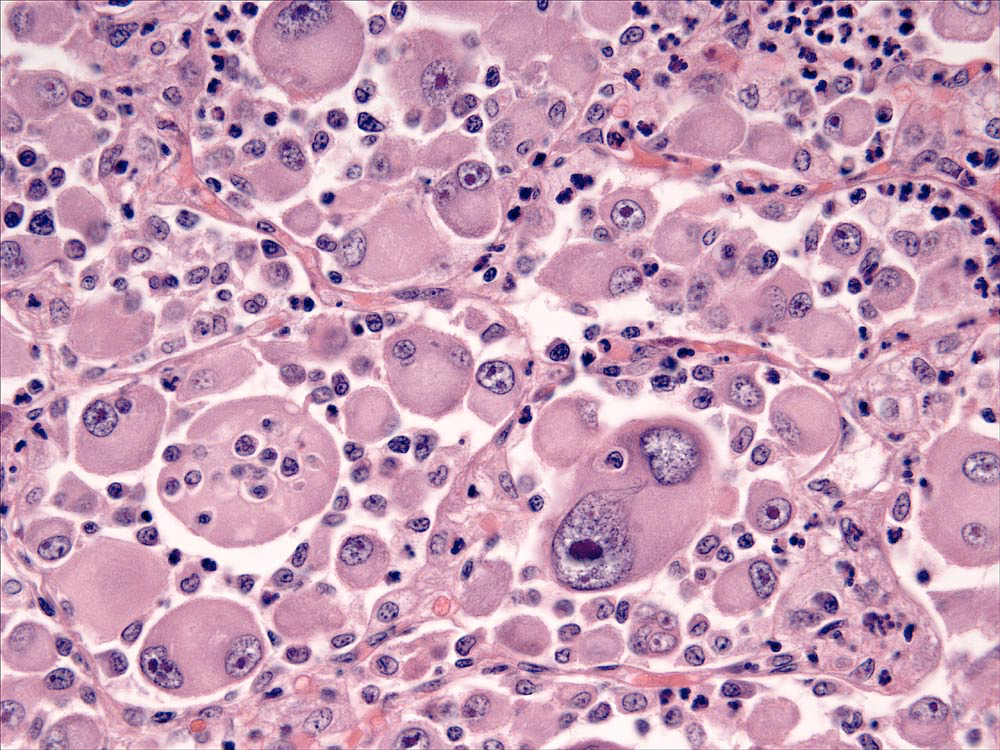

Lesions of HS are composed of sheets of large, pleomorphic, mononuclear and multi-nucleated giant cells, which usually have marked cytological atypia (Fig. 2), and numerous bizarre mitotic figures. Some lesions may consist of spindle cells, either alone or mixed with the mononuclear and multinucleated giant cells. Pure spindle cell lesions often lack discrete cell borders and resemble spindle cell sarcomas of diverse cell lineage (fibroblast, myofibroblast and smooth muscle origin). Confirmation of histiocytic lineage is best achieved with IHC in these instances. Phagocytosis of red cells, leukocytes and tumor cells occurs in HS, but it is not usually pervasive except in hemophagocytic HS.

Immunophenotypic Features

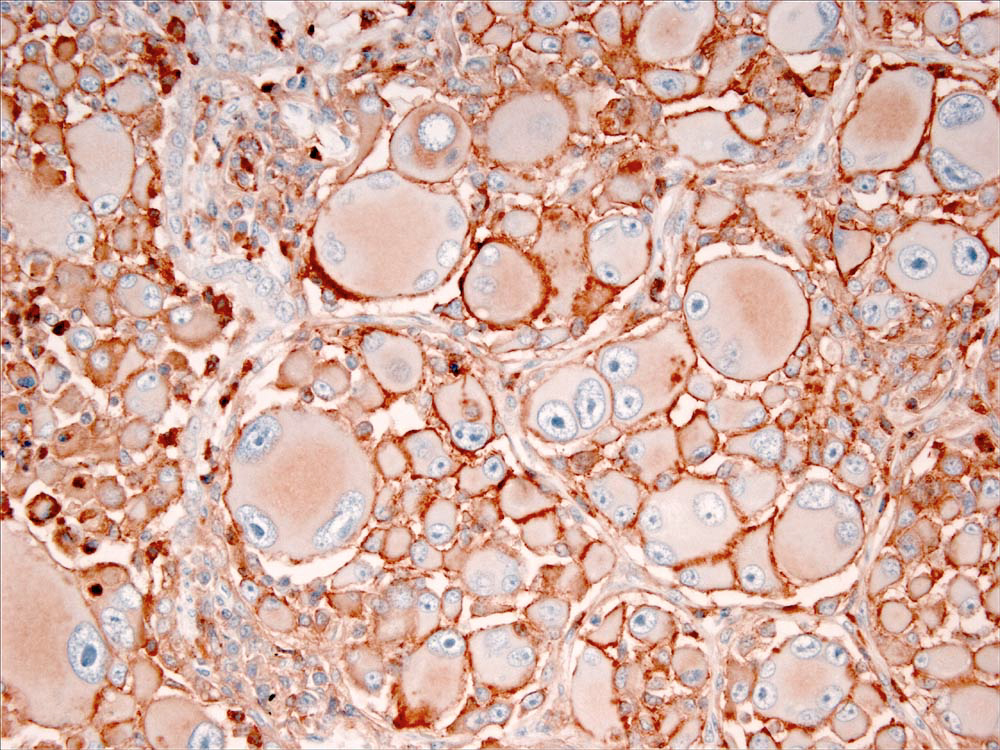

Immunostaining of most HS lesions reveal that tumor histiocytes express leukocyte surface molecules characteristic of interstitial DCs, which include CD1a, MHC class II and CD11c/CD18. Expression of CD4 by neoplastic histiocytes has not been observed in HS. In comparison, histiocytes in canine reactive histiocytoses regularly express CD4, which indicates an activation phenotype. The β-2 subunit of the leukointegrins (CD18) is readily demonstrable in formalin-fixed tissue sections of HS lesions (Fig. 3). Since lymphomas may express abundant CD18, it is important to exclude a lymphoid origin (e.g. large cell lymphoma) by staining for lymphocyte antigen receptor associated molecules (CD3 and CD79a), and CD20. The exact sub-lineages of DCs involved in HS have not been determined in most instances. The most likely candidates include interdigitating DCs in lymphoid tissues and perivascular interstitial DCs in other involved tissues. In hemophagocytic HS, histiocytes express markers most consistent with macrophage differentiation (CD11d/CD18) rather than DC differentiation, in which abundant expression of CD1a and CD11c/CD18 is expected.

-TOP-